Iranian Migrant Stories from Bahrain, 1920-1950

My ongoing research project involves combing through cases from the British Political Agent's Court in Bahrain to trace social networks and uncover the social history of these migrants. Some were merchants, but many were "bread makers," carpenters, and day laborers who left the south of Iran in the first half of the twentieth century to make a new life on the western shores of the Gulf. I have featuring some of the rich and fascinating stories below. The Many Homes of Ghulam Ali Jahromi

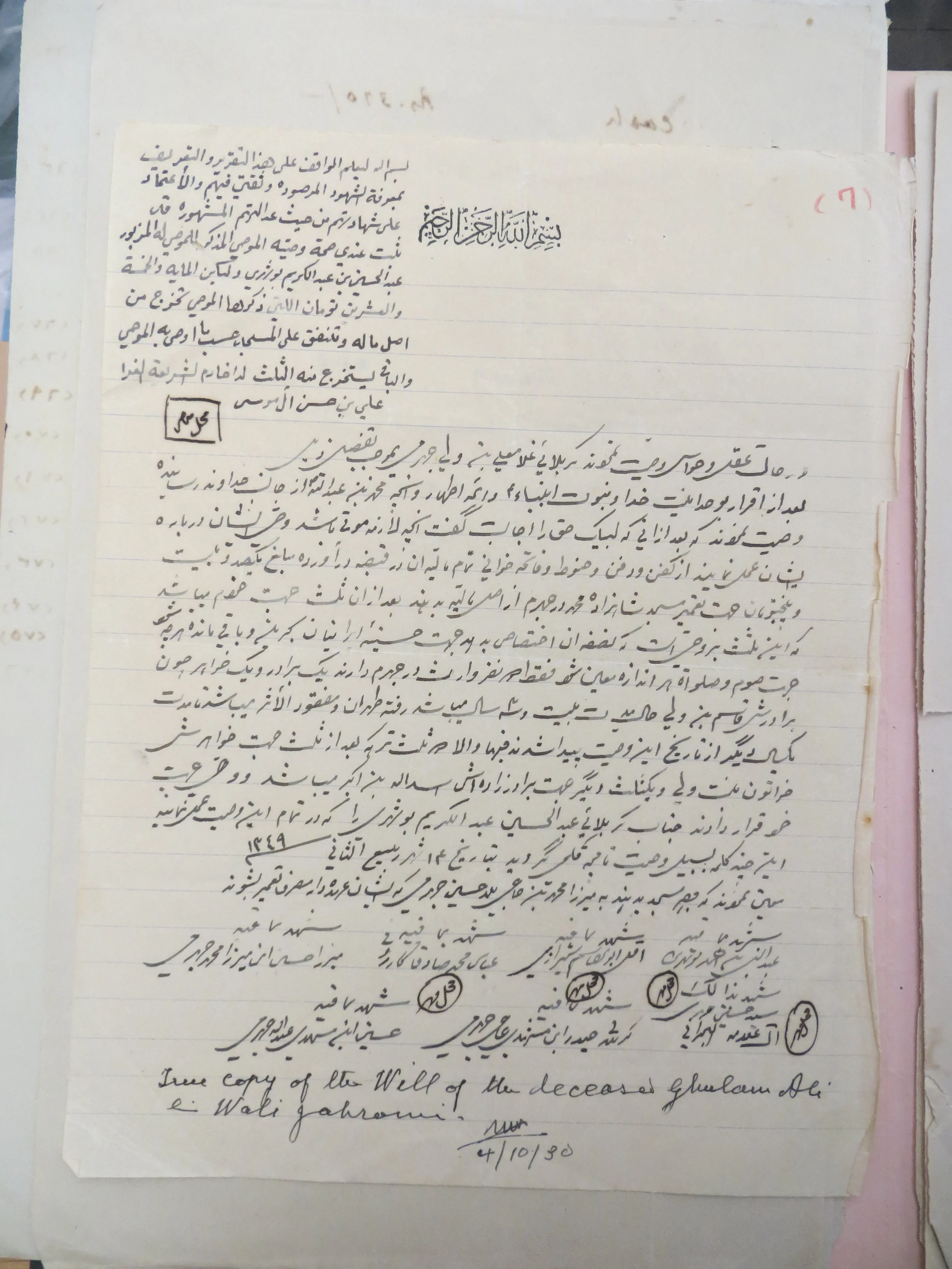

Ghulam Ali bin Wali Jahromi was a man of little means, but clear ideas about how his possessions should be divided. Ghulam Ali’s will is instructive for us in understanding how even people not wealthy enough to return to Iran often still felt very connected to the communities they left behind – although perhaps equally connected to the transplants of their communities in Bahrain.

When he begins to feel unwell he calls to his side a Shi’a qadi, three prominent Shi’a iranian merchants, three men also from Jahrom (in Iran), and an Arab Bahrani. Perhaps the diversity of the crowd of witnesses he brought together was intentional in order to keep them honest.

With his modest estate he divides his Iranian money (toman) into three parts:

-To repair a mosque back in his hometown of Jahrom (the person who was to take the money there was present)

-A donation to the big Iranian Husseiniyya of Bahrain (run by the family of one of the merchants present)

-For praying and fasting

From the remainder of his wealth and rupees he allocated 2/3 his sister in Jahrom and 1/3 to his nephew. He had lost track of his brother who went to Tehran almost twenty years prior and had never heard from him again.

Source: India Office Records, R/15/3/6559

IOR R/15/3/28

Too Many Fatmahs

Bittersweet Eid Treats

In 1944 Fatmah al-Gabandi, an Iranian was contracted to work for Fatmah, a Qatari for all of Ramadan cooking in her home. The agreed compensation was 5 Rs and a Kiswa (a long embroidered dress). When Iranian Fatmah returns on the night before eid to claim her compensation, Fatmah her employer tells her to go and fetch water. Now Iranian Fatmah might have been poor, but she was no servant, and she was only being paid to cook and clean. When she refused to bring water, Fatmah al-Gabandi alleged that the Qatari Fatmah attacked her and tore her dress. We never find out exactly what happened because the case was settled outside of court.

The Iranian Fatmah appears to be quite poor as she was working for less than a rupee per day. Other laborers earned 3-4 rupees per day. Along with her last name, the fact that she was living in the house of al-Qusaybi (Ibn Saud’s representative in Bahrain) suggests that she was Sunni. She was probably unmarried and living with her parents there. She also lived in the same neighborhood as her employer, suggesting that the neighborhood was stratified economically. While women often worked, they were usually independent and not contracted as laborers like those from the first vignette.

Like many others much poorer than herself, Fatmah was willing to pay the 3-Rupee court fee to have her case heard. It is impossible to know how she knew about the court or why she thought it worth her trouble, but she is amongst hundreds and perhaps thousands of Iranians who take their cases to court in order to claim a meager monetary reward, and sometimes only the satisfaction of knowing they were right.

Source: India Office Records, R/15/3/2394